India

“India ranks with East and South Africa as one of the world’s great wildlife destinations. It has one of the largest populations of tigers, one of the world’s most spectacular bird reserves at Bhagalpur, and habitat and reserves that range from the high Himalayas to the Ganges Delta.”

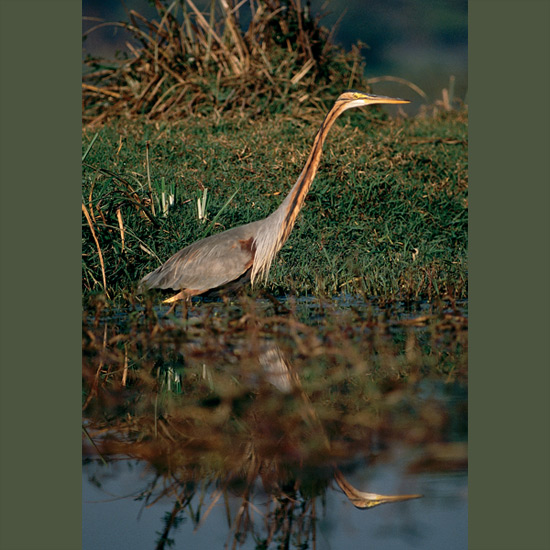

This teeming country, so large and various it is known as the Asian subcontinent, has rare animals equal to its natural beauty, from splendid Bengal tigers, diminutive marbled and golden cats, fearsome king cobras, and delicate chital deer to clouded leopards in high, remote Himalayan reserves.

Its national bird is the strutting technicolor-hued peacock, sometimes in flocks of dozens.

Wildlife conservation roots go back to the third century BC. Prime Minister Kautilya then codified the “Arthasashtra” establishing protected areas and advocated creation of the first wildlife sanctuaries or “abhayaranyas.” In the next century, Emperor Ashoka issued his Fifth Pillar Edict forbidding slaughter of many animals and burning of forests. The edict also established sanctuaries. This followed an Indian tradition going back even further, when at the dawn of history natural groves were declared sacred and inviolate from human disturbance.

The modern Indian Constitution stipulates, “the State shall endeavor to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and the wildlife of the country…(this) shall be the duty of every citizen, and to have compassion for living creatures.”

Now more than 550 national parks and sanctuaries are reserved for wildlife here.

However, needs of a burgeoning population—at recent count, over one billion persons—have conflicted with those of wildlife.

India’s great forests are largely gone. Overhunting has driven some animals to extinction, others to the brink of it. Poaching is ever-present and serious, despite efforts like Project Tiger, undertaken by the Indian government at the behest of World Wild Fund for Nature to rescue this magnificent animal whose numbers by 1962 were reduced to several hundred in the wild.

Click image for details.

Education as much as protection is necessary. A poor peasant trying to feed a large family can find it hard to understand why a tiger could be worth more alive than dead, when its corpse can bring him many times his annual income—up to $10,000 U.S. in China for its skin, teeth, bones, flesh. Every part of a tiger brings top prices for illegal resale as a trophy or supposed aphrodisiac, or oriental folk medicine cure for a wide array of human ills.

At least as damaging to wildlife is use of lethal pesticides and habitat destruction for agriculture, dam construction, logging, and mining.

There are successes. Many of India’s outstanding wildlife reserves and national parks formerly were hunting grounds of maharajahs and India’s British rulers. At KEOLADEO GHANA NATIONAL PARK, popularly known as Bharatpur, thousands of birds used to be killed for sport in a single day. Now hundreds of species live under protection and some fly thousands of miles crossing the high Himalayas to reach this welcoming place.

Massive one-horned rhinoceros, once down to a few dozen on plains they had roamed in the tens of thousands, now are protected and have been brought back to viable populations at a few reserves, especially KAZIRANGA (see p.216) in Assam.

These victories have helped others besides target species. Sanctuaries established for the purpose of saving one or more threatened animals have in the same habitat saved a whole ecosystem of insects, birds, fish, lizards, butterflies, trees, and flowering plants.

The value of these places is made clear by contrasting them with immediately surrounding areas. Inside, habitat is lush and full of natural creatures; outside their boundaries the land is often devoid of natural activity, cleared for uses incompatible with the natural environment.

Without these sanctuaries, India’s impressive wildlife would be greatly reduced and many species would be gone. Due largely to their existence, India still has over 2,000 species and subspecies of birds, more than 350 species of mammals, more than 700 species of reptiles and amphibians, some 50,000 kinds of insects including large and colorful butterflies, and more than 45,000 plants ranging from those of dry desert scrub to mountain meadows. Over 15,000 of the plants are endemic.

It should be noted that some reserves close during monsoon season—best check ahead.

India

BHARATPUR (KEOLADEO GHANA) NATIONAL PARK

PERIYAR NATIONAL PARK AND TIGER RESERVE

SARISKA TIGER RESERVE NATIONAL PARK

SUNDERBANS NATIONAL PARK as well as...

Narcondum

Mahuadaur

Pirotanis

Valley of Flowers

More about the Reserves in INDIA

Each button selection will take you to a site outside the Nature's Strongholds site, in a separate window so that you may easily return to the reserve page.

Advertisement