Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge

Millions of birds from six continents find their way to Alaska’s Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge every spring. They come to this vast coastal plain to raise families on these 40,625 square miles (105,250 km2) of lakes, ponds, and streams—one of the wildest, largest, most isolated wildlife reserves in the world.

It is an extraordinary sight, the air literally filled with flying, calling birds—waterfowl, shorebirds, and passerines—all in handsome breeding plumage for courtship, mating, and family duties in the safety of this ecosystem teeming with fish and insectivorous food for nestlings. All this must be accomplished during the short arctic summer between June ice-breakup and early fall, August or September at the latest.

Golden plovers, bar-tailed godwits, and rare bristle-thighed curlews arrive after non-stop flights of 2,000 miles (3,225 km) or more over open ocean from islands throughout the South Pacific, some from Australia. Whimbrels, black-bellied plovers, surfbirds, black turnstones, dunlins, and rock, least, and western sandpipers travel along the Pacific Coast; solitary, pectoral, and semipalmated sandpipers take inland routes from as far south as Cape Horn or Tierra del Fuego.

Eighty percent of the world’s emperor geese are here, and most of the tundra swans of both Pacific and Atlantic flyways. Arctic terns fly up to 22,000 miles (35,400 km) round-trip—longest migratory journey of any creature.

No other area of similar size may be so critically important to survival of so many kinds of water-oriented birds.

Small birds find their own places—redpolls, snow buntings, Lapland longspurs, savannah, tree, and fox sparrows, gray-cheeked thrushes with Asian visitors such as arctic warblers, northern wheatears, and yellow wagtails. Fierce raptors include golden eagles, rough-legged hawks, and gyrfalcons. There are long-tailed and parasitic jaegers, Pacific and red-throated loons—altogether 145 breeding bird species.

Huge numbers of fish as well—from fingerlings to enormous Dolly Vardens, grayling, burbot, whitefish, northern pike—inhabit every body of water. Millions of salmon swim up the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers to spawn—chinook (king), coho, sockeye, chum, and pink—and beluga whales and occasional walruses come up rivers in early spring.

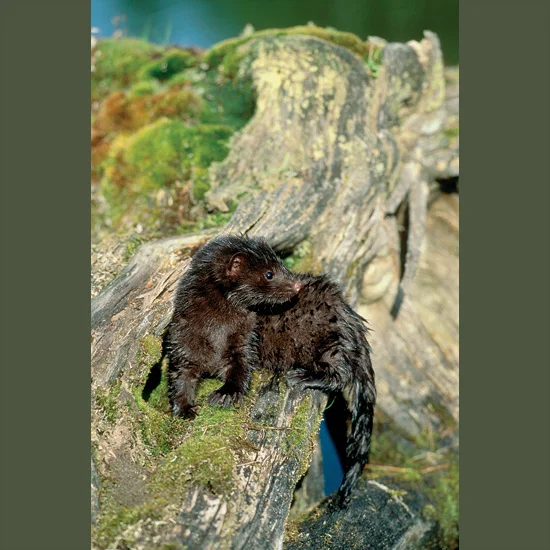

Mountains on the east side of the refuge rise to 2,000 feet (615 m). Almost all Alaska’s land mammals are there—black and brown bears, moose, caribou, red and arctic foxes, timber and arctic wolves, wolverines, otters, mink, muskrat, tundra hares.

But birds own this refuge, its fragile habitat uniquely suited to their needs.

Visits are not easy to arrange. Trips should be planned well in advance and checked with refuge headquarters in Bethel, reachable by commercial air from Anchorage. Bethel has lodging and it’s possible to charter flights over the refuge, arrange to be put down for a week’s camping and picked up later—restricted tent camping sometimes permitted—or ride with a scheduled mail plane to an Inuit village where guides may be available.

Best time is June but weather can be rainy, overcast, and windy, anytime. Warm clothing is always prudent; hip boots useful almost everyplace.

Visits are not easy to arrange. Trips should be planned well in advance and checked with refuge headquarters in Bethel, reachable by commercial air from Anchorage. Bethel has lodging and it’s possible to charter flights over the refuge, arrange to be put down for a week’s camping and picked up later—restricted tent camping sometimes permitted—or ride with a scheduled mail plane to an Inuit village where guides may be available.

Best time is June but weather can be rainy, overcast, and windy, anytime. Warm clothing is always prudent; hip boots useful almost everyplace.

Nunivak Island, 1,719-square-mile (4,450-km2) unit of Yukon Delta 20 miles (32 km) located west of the Alaskan coast in the Bering Sea, is main home today of great, shaggy Alaskan musk-oxen which once roamed over much of Asia and North America. Musk-oxens’ historic defense—forming a circle with massive horns pointed outward—was effective against wolves but no match for repeating rifles and, by 1920, indiscriminate slaughter had decimated their numbers. Protection here has stabilized them and some have been taken to restart nucleus herds elsewhere.

These bulky animals are not easy to see even here though they stand four feet (1.2 m) high at the shoulder with long fur draped almost to their feet, since they can space themselves widely over this large tract. But Nunivak is a fascinating island in any case, with a large reindeer herd and some of the world’s largest seabird nesting colonies for kittiwakes, murres, pelagic cormorants, horned and tufted puffins, parakeet and crested auklets, and pigeon guillemots as well as songbirds, including rare McKay’s buntings, winter visitors which nest only on Bering Sea islands.

Restricted tent camping is permitted and it is sometimes possible to stay with local families. Best way is to fly to Mekoryuk, Nunivak’s only village, and hike out from there or arrange to go by boat (a somewhat hazardous trip) in summer or by snowmobile in winter (it’s cold then but often bright and beautiful). In any case, visits should be planned as far ahead as possible in consultation with refuge staff.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

Advertisement