The Everglades (Florida)

The Everglades is a wildlife-rich wetland ecosystem unique in the world—literally a “river of grass” protecting a delicate web of life with more threatened and endangered species than anyplace else in the U.S.

This 2,344 square-mile (6,070-km2) area, much of which is now protected as a National Park, World Biosphere Reserve and U.N. World Heritage Site, is the world’s largest freshwater marsh. Its origins are 250 miles (402 km) north of the Florida toe in the headwaters of the ancient, formerly meandering Kissimmee River. From there historically water entered and spilled over the banks of Lake Okeechobee, seeping along in a gradual southward path 50 miles wide and 100 miles long (80 × 160 km), until it finally reached Florida Bay and the gulf. Along the way its mixture of slow-moving water, sunlit vegetation, and teeming microorganisms provided homes and nourishment for a prodigious wildlife community.

The Everglades has kaleidoscopic-hued birds like purple gallinules and painted buntings; frigate or man-o-war birds inflating scarlet throat balloons; brown and white pelicans with up to nine-foot (2.7-m) wingspreads. Anhingas—whip-necked “snake birds”—stand like statues so the sun can dry their feathers after a swim. Golden warblers of a dozen species stop over in the thousands in migration.

Black skimmers ply waters with lower mandibles dropped, snapping shut to trap small organisms for their dinner. Swallow-tailed kites soar overhead in spring and stay to nest. Scarlet-crested pileated woodpeckers hammer pine trees with blows that resound over the marsh.

Rare short-tailed hawks are here with similarly uncommon Cape Sable seaside sparrows and white-crowned pigeons, mangrove cuckoos, and black-whiskered vireos.

Snowy, carmine-crowned whooping cranes, one of the world’s loveliest and most endangered birds, range over upland sections of the Kissimmee in a newly-established flock associating with stately sandhill cranes. Watching from bare branches are caracaras, uncommon colorful raptors.

The list is too long to enumerate here. Altogether there are more than 400 bird species.

The Everglades has kaleidoscopic-hued birds like purple gallinules and painted buntings; frigate or man-o-war birds inflating scarlet throat balloons; brown and white pelicans with up to nine-foot (2.7-m) wingspreads. Anhingas—whip-necked “snake birds”—stand like statues so the sun can dry their feathers after a swim. Golden warblers of a dozen species stop over in the thousands in migration.

Black skimmers ply waters with lower mandibles dropped, snapping shut to trap small organisms for their dinner. Swallow-tailed kites soar overhead in spring and stay to nest. Scarlet-crested pileated woodpeckers hammer pine trees with blows that resound over the marsh.

Rare short-tailed hawks are here with similarly uncommon Cape Sable seaside sparrows and white-crowned pigeons, mangrove cuckoos, and black-whiskered vireos.

Snowy, carmine-crowned whooping cranes, one of the world’s loveliest and most endangered birds, range over upland sections of the Kissimmee in a newly-established flock associating with stately sandhill cranes. Watching from bare branches are caracaras, uncommon colorful raptors.

The list is too long to enumerate here. Altogether there are more than 400 bird species.

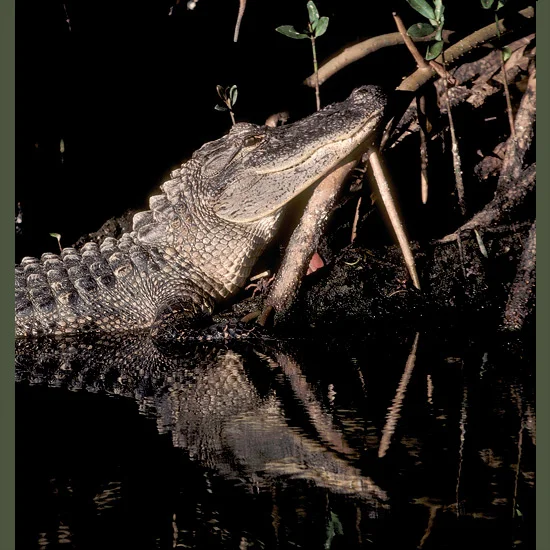

Below them in the waters are river otters and endangered crocodiles (tell them from alligators by their underslung jaws) and, in drier sections, bobcats, white-tailed deer, and black bears—altogether over 40 mammal species among some 600 kinds of animals (not counting 40 species of mosquitoes!).

Five endangered species of ponderous sea turtles crawl up the beaches in summer to lay eggs.

There are more than 1,000 seed-bearing plants and 24 epiphytic orchids.

This incomparable area has come under serious threat in recent decades from two directions: encroaching population—Florida’s warm climate attracts 900 new occupants every day—and agricultural activities which have added pesticides and fertilizer to water sent into the Everglades. Agricultural demands also have interrupted water timing with disastrous effects on natural reproductive cycles (shorting water supplies as well for metropolitan areas like Miami which draw from the same aquifer).

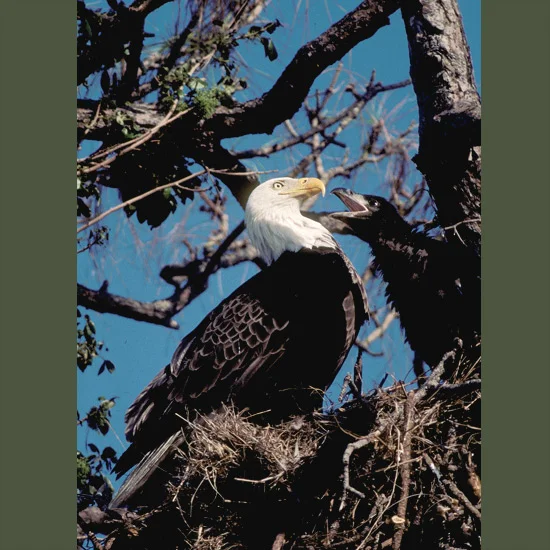

Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge, with 41 square miles (106 km2) adjoining Big Cypress National Preserve, protects endangered Florida panthers, also black bears, bobcats, otters, alligators, wood storks, varied birdlife. Some sections closed to public use. Also administered from this office is Ten Thousand Islands National Wildlife Refuge, 31 square miles (81 km2) of coastal estuaries just north of Everglades National Park—a last remaining stretch of undeveloped Florida coastline, protecting breeding and feeding grounds for fish, endangered manatees, sea turtles, bald eagles. Tel: (+1) 239-353-8442.

Not part of the Everglades but with similar birdlife and well worth side trips are Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge at Sanibel Island off Fort Myers on the Florida west coast; Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, off Titusville further north on the east coast; and for snorkelers and scuba divers, dazzling Biscayne National Park, with the northernmost U.S. coral reef, offshore southeast of Miami; and farther south, off Key Largo, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park.

Last stand of southern bald eagles was in the Greater Everglades ecosystem after DDT pollution thinned eggshells and for a time brought hatching populations of this magnificent national symbol close to extinction.

Florida panthers, only a few dozen left in the wild, are stealthily at home here. It is a major nesting place for rare wood storks and sunset-hued roseate spoonbills, whose odd-shaped mandibles swish about in the shallows to exploit a special food-gathering niche. There are wailing limpkins and fierce-looking Everglade kites, both of whose numbers crashed when their sole food source, apple snails, lost habitat.

Alligators boom mating calls through the night and stand guard over warming vegetation nests, gently nudging their eggs to check incubation progress. Finally, with careful razor-toothed jaws, they pick up their young and carry them to water.

Great egrets, glossy and white ibises, snowy egrets, tri-colored herons, great blue and great white herons, yellow-crowned and black-crowned night herons, as well as green-backed and little blue herons all are here. Exquisite courtship plumes threatened their survival when demand for them to decorate ladies’ hats raised their world price per pound over that of gold. Plume-hunters defeathered birds alive and left both adults and helpless young to perish on their nests. An Audubon warden engaged to protect them was murdered. Public outrage forced a halt to the cruel slaughter.

Wading bird populations once estimated at two million (250,000 white ibises alone) recently have been down as much as 90 percent. Some species no longer may have viable self-sustaining nesting populations.

Remedial measures are beginning to help. Congress has directed The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to implement a restoration plan that includes land purchases to hold water for timely release coordinated with the Everglades’ natural cycle and clean-up of damaging agricultural runoff in a federal-state partnership. It will be the largest ecosystem restoration ever undertaken. Where a start has been made, the situation has improved and wildlife has responded. The Kissimmee River, channelized in an ill-conceived engineering project, is being re-dug in a natural, meandering path, which already has attracted renewed life of all kinds.

Centerpiece among tracts set aside to protect sections of the Greater Everglades ecosystem is world-renowned Everglades National Park. Others include Big Cypress National Preserve; Lake Okeechobee and Lake Kissimmee; Corkscrew Swamp Audubon Sanctuary; Florida Bay; Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve; and three national wildlife refuges—Loxahatchee, Ten Thousand Islands, and Florida Panther.

Best times to go are October–May. Summers are hot, humid, buggy.

International airlines fly to Miami, where car rentals are available to drive to three national park access points:

To main park headquarters and entrance, take Florida Turnpike south to Florida City, then FL Route 9336 to park entrance and headquarters.

Shark Valley entrance is at northern boundary, 35 miles (56 km) west from Miami on US 41.

Everglades City, on the park’s western edge, borders the watery Ten Thousand Islands area, 4.8 miles (8 km) south on FL Route 29 from Tamiami Trail intersection to visitor center.

ALSO OF INTEREST

Big Cypress National Preserve contains 1,138 square miles (2,946 km2) of spreading prairies dotted with cypresses, deep pools, and sloughs, with wading birds, including some storks, also panthers, a few endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers. Limited access; best seen from the (sometimes rough) Loop Road and Turner Road. Compromises in its set-aside permit mineral exploration and hunting—so best avoid hunting season, mid-November–December. Visitor information at Oasis Ranger Station on Route 41, halfway between Naples and Miami, or Tel: (+1) 239-695-4111.

Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, a National Audubon Society sanctuary, has largest U.S. nesting colony of wood storks and world’s largest remaining subtropical old-growth bald cypress forest—also wading birds, barred owls, limpkins, otters and, in spring, warblers and painted buntings, with an excellent two-mile (3.2-km) boardwalk. Fifteen miles (25 km) east of I-75 Exit 17; or from Naples (nearest good lodging) drive nine miles (15 km) north to U.S. 41, 21 miles (35 km) east on FL Route 846; left at sanctuary sign. Tel: (+1) 239-687-3771.

Fakahatchee Strand State Preserve—97 square miles (250 km2) of forested swamp, seven miles (11 km) west of Route 29 on Route 41—shelters Florida panthers, black bears, Everglades mink, wood storks, North America’s last stand of native royal palm trees, and largest concentration and variety of (protected!) native orchids.

Take Big Cypress Bend boardwalk off US 41 or a day hike on a logging tram road—maps available at ranger station on Route 29 north of Everglades City. Tel: (+1) 239-695-4593.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

Advertisement