Okefenokee National Wildlife Refuge (Florida-Georgia)

One of the great primitive wildernesses of the world—a dark, brooding cypress swamp with wet prairie openings, its only sounds those of natural communications: musical frogs’ chorusing, owls twittering, minnows splashing, wildcats’ screams, wind blowing through rain-spattered trees, herons squawking. Alligators bellow for mates, and wild turkeys gobble for theirs.

One of the largest alligator populations anywhere is here—10,000 or so of these primitive reptiles, once close to extinction, that grow up to 13 feet (4+ m) long, and whose offsprings’ sex is determined by their temperature as incubating eggs in the nest.

Graceful, long-legged wading birds gather in the hundreds—herons, egrets, ibises, endangered storks—roosting and nesting in colonies covering many acres.

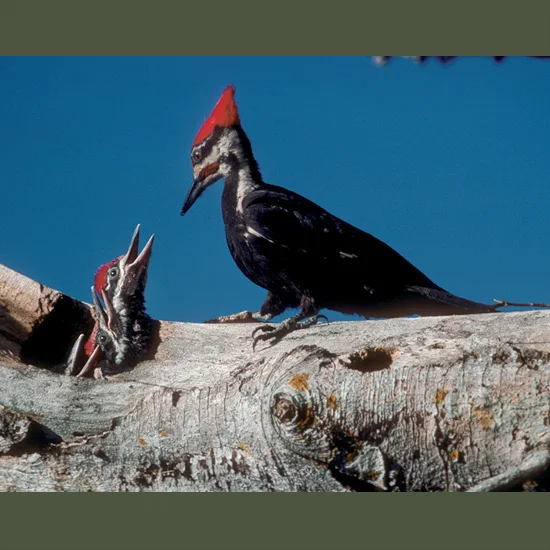

Flame-crested pileated woodpeckers a foot long (30+ cm) hammer for grubs on moss-hung cypresses. Endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers search out tall pines so old their centers have turned to soft “red-hearts” ideal for nest hollows. As they drill holes for them, sap runs down the trunks, deterring predation by hungry snakes.

This is one of the last southern U.S. strongholds for lumbering 400-pound (180-kg) black bears. These adaptable intelligent mammals have disappeared from much of their former territories, replaced by land development, driven off by persecution.

Here too are handsome, gentle indigo snakes, a threatened, non-poisonous New World snake— and some of its poisonous relatives, cottonmouths, coral snakes, and three kinds of rattlers.

Bobcats, white-tailed deer and, possibly, endangered Florida panthers prowl quietly along forest paths which, it is hoped, will one day link Okefenokee with Pinhook Swamp and Osceola National Forest in a wildland corridor offering more protection for larger mammals.

Families of river otters, swift enough to catch any fish, porpoise through waterways, sliding down banks in playful games. Gorgeous wood ducks, called the world’s most beautiful waterfowl, nest in tree cavities from which downy ducklings emerge and drop safely 40 feet (12 m) immediately after hatching. Migratory ducks of a dozen species—teal, shovelers, gadwalls, redheads, ring-necks—come for the winter.

A variety of orchids bloom in remote areas, where crimson-lipped carnivorous sundews and pitcher plants set sticky traps for insects.

Golden prothonotary warblers find nest sites in tree cavities low over the water. Parulas higher up weave snug cups of Spanish moss, not bothered by omnipresent brown-headed nuthatches, yellow-billed cuckoos, wood pewees, and Carolina wrens, but warily watchful for Cooper’s and red-shouldered hawks. Chuck-will’s-widows tirelessly announce and re-announce their names and territorial rights throughout spring nights.

Moist open prairies are abloom with golden club and sunflowers. Crimson-crowned Florida sandhill cranes leap high in spectacular courtship dances, proclaiming their mating union with one of the wildest cries in the animal kingdom.

White ibises fly up by the hundreds from marshes that stretch golden in the sun as far as the eye can see. (Bitterns are here, but less easily seen, stretching motionless in a disappearing act against reeds.)

Altogether some 235 bird species, 50 mammals, 64 reptiles, 37 amphibians, and thousands of plants make their homes on these 619 square miles (1,600 km2) covering adjoining parts of the southeastern states of Florida and Georgia, and named for the Seminole word meaning “Land of Trembling Earth.” The name denotes what happens when 15-foot-deep (5-m) peat beds explode continually from a vast bog of ancient geologic origin—once part of the ocean floor—sending to the water’s surface new islands which quake at a footfall even after they are firm enough to support tall trees.

The Okefenokee is headwater of two major rivers—the famed Suwannee which empties 270 miles (450 km) west in the Gulf of Mexico, and the St. Mary’s which flows 50 miles (83 km) east to the Atlantic Ocean.

The wonder of this multifaceted ecosystem is in the sum of intricately combined workings of thousands of separate natural components each with its necessary niche. Tiny colorful spiders watch over delicately balanced webs hung with jewellike crystalline droplets. Massive mossy cypress trees stand as they have for centuries against crimson sunsets while waves of birds fly to nightly roosts past alligators’ eyes glowing red in day’s last light.

Perhaps the greatest wonder is continued existence at all of this 619 square miles (1,600 km2) of freshwater marsh, pine uplands, islands, lakes, and dense forest swamps set aside in Florida and Georgia after efforts of more than half a century to drain its wetlands and destroy its primeval forests and their wondrous inhabitants forever.

Best times are February–May and October–December (but it’s always interesting). Motels are nearby at Folkston, Waycross, and Fargo in Georgia. Campgrounds are near Folkston, also in nearby state and county parks; also, by prior arrangement well in advance, along refuge canoe trails—more than 80 miles (135 km) of them.

To get there from Jacksonville, Florida, international airport take I-95 north to Kingsland exit, then Route 40 to Folkston, Georgia. Main entrance and visitor center is 11 miles (18 km) southwest of Folkston off Route 121/23. There are walking and biking trails, boardwalks, observation towers, and guided boat, canoe, and night tours.

Advertisement