Mana Pools National Park

African guides regard Mana Pools as the Garden of Eden and little wonder. No place else in the world may combine the lush, wilderness character of this 845-square-mile (2,190-km2) national park with stunning vistas that seem to go on forever, where wild animals like lions, elephants, and buffalo roar, trumpet, snort and behave much of the time as if they have never seen a human being or tourist van.

Some of the highest concentrations of wildlife on the continent are seen in this U.N. World Heritage Site.

Focus of this natural richness is the lower Zambezi River, 1,675 miles (2,700 km) long, which originates in uplands of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire) near Africa’s continental divide. Heading south toward the Indian Ocean, it enters Zimbabwe at Victoria Falls in a spectacular cataract that is one of the wonders of the world, and joins Lake Kariba, one of the great man-made lakes of the world, and then reaches Mana Pools.

“Mana,” meaning four, refers to the four largest perennial pools left as the river shifted course over thousands of years, pools which are the main water source around and attract huge numbers of animals. A recent census counted some 6,500 elephants, 16,000 buffalo, 2,000 hippopotami, several hundred endangered black rhinoceros and, among hoofed species, herds of hundreds of zebras, sable antelopes, kudus, elands, and waterbucks, along with thousands of birds of woods, water, and grasslands.

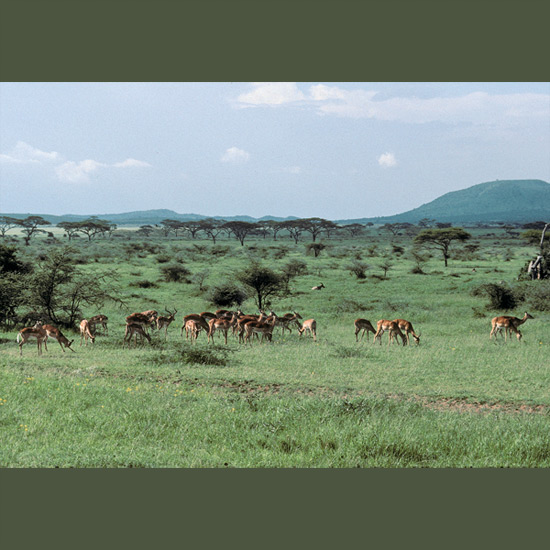

Arrayed among the watercourses on a flat floodplain which goes on for miles, surrounded by terraced banks which seem designed by a park-planner’s hand, are graceful impalas in herds of200 or so. Large groups of other grazers and browsers include elands, kudus, massive buffalo, endangered black rhinoceros, occasional rare nyalas, and stubby warthogs. Each species has cropped the vegetation at various levels determined by their own dental equipment and stature. As a result acacia, mahogany, and mopane trees and, lower down, shrubs and grasses all are sheared off at perfectly even heights. This gives them a park-like, almost dreamlike appearance over which the strong sun, filtered through the greenery, casts a gold-green light against a backdrop of the river’s escarpment which rises suddenly and dramatically 3,300 feet (1,000 m) in places along both sides of the river, both here and across the way in Zambia.

A canoe safari of three to nine days is a wildlife experience unlike any other, moving silently through these waters, getting out and walking from time to time (Mana Pools is one of the few national parks where one is permitted to get out and walk), sleeping in tents along the way and listening to night sounds.

Pods of hippos submerge to keep sensitive skins moist and cool during the day, showing only dozens of round eyes above the surface. One avoids startling them; they can become dangerously enraged at disturbance. At night, these two-ton-or-so (1,800-kg) beasts haul themselves out and forage, their presence evident from plodding footfalls and crunching sounds as they crop the grasses.

Carmine and white-fronted bee-eaters fly up in rosy and azure clouds from colonial nest holes along riverbanks in September.

Elephants in placid family groups bathe, or stand on termite mounds to reach a high acacia branch. Occasionally a mother will flap large ears in warning and make a mock charge. Sometimes they spray water on canoeists. A low reverberation may be an elephant’s “tummy rumble” (but it comes from vocal cords) notifying others of the canoe’s presence. Unheard may be infrasonic vibrations from forehead nasal passages telling companions several miles away that a canoe has arrived.

Baboon troops of 50 or so swing about, a sudden rasping scream revealing that a predator, perhaps a secretive, nocturnal leopard, has been discovered napping on a tree limb. Leopards are so perfectly concealed by their gorgeous, dappled fur they are seldom noticed unless they move, and not always then. Lions are less retiring and may growl when a canoe appears.

A 10-foot (3-m) crocodile slides into the water. More than 1,000 of these ancient saurians, unchanged in 70 million years, live in Mana Pools and nest on midstream islands.

A dark underwater shape may be a primitive lungfish, member of a group that has survived for more than 400 million years, breathing air with a single lung.

Over 380 bird species are here. Livingstone’s flycatchers flirt rufous tail fans as they hawk flying insects in riparian woodlands. Skimmers lay speckled eggs in shallow nest scrapes and ply thewaters with bills agape for small fish, whose contact instantly causes these formidable lower mandibles to snap closed. Hundreds of red-winged pratincoles rise in spiral columns, catching warm-air thermals. White-winged pratincoles nest colonially on rock outcrops in Mupata Gorge and emerge in swallowlike swarms at dusk.

Brilliant little Angola pittas, special treat for birders, nest in untidy domes in thorntrees. Lilian’s lovebirds chatter in flocks of hundreds in mopane and acacia woodlands. Rare rufousbellied herons snatch up frogs in Chirundu flood channels.

Curly-horned kudus come to drink and only lift their heads with curious expressions as the canoe glides by.

ALSO OF INTEREST

Chizarira National Park is rugged, remote wilderness with abundant wildlife including elephants, buffalo, elands, Sharpe’s grysboks, klipspringers, tsessebes, rich birdlife.

Gonarezhou National Park is potentially a great reserve, with prolific populations of hippos, oribi, klipspringers, rich birdlife including such rarities as hooded vultures, blue-spotted doves, Pel’s fishing owls, but serious problems with poaching, especially from Mozambique.

Matobo National Park is part of the rocky Matobo range with impressive white rhinos, giraffes, zebras, and dense (though seldom seen) leopard population; renowned for birds of prey, especially black eagles.

Matusadona National Park comprises a virtually untouched wilderness along the southern shore of beautiful Lake Kariba with an enormous buffalo population, also abundant elephants, kudus, impalas, some black rhinoceros. Leopards are occasionally seen in Santati Gorge. Walking safaris, also wildlife viewing from boats.

Victoria Falls National Park and Zambezi National Parks—Victoria Falls, a wonder of the world and World Heritage Site, is the largest sheet of falling water in the world—over 150 million gallons (625 million liters) a minute in flood season. Just below the falls, water thrown up by it sustains a magnificent rain forest populated by fascinating plant and animal species, among them African goshawks, African green pigeons, trumpeter hornbills, yellow-bellied bulbuls, collared sunbirds. Rare Taita falcons breed on the cliffs. In gorges below are gray-rumped swallows,African swifts, rock martins, familiar chats, and mocking cliff-chats. Some of the world’s most exciting white-water rafting is in the gorges below the falls. Zambezi National Park, adjoining, is known as well for abundance of sable antelopes, elands, buffalo, giraffes.

Click image for details.

Visit Tripadvisor®

for lodging information about this Reserve

Advertisement